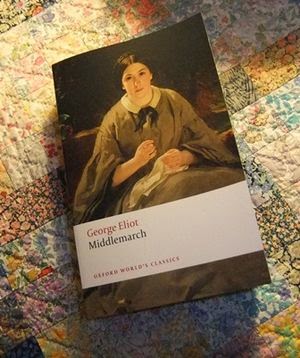

I’m sitting on my balcony, reading Middlemarch. It strikes me as a rare

treat, two or three times a year, that enough time has elapsed since I’ve read

it last for me to feel it freshly, and I pull it off my bookshelves and delve

into its wisdom. I have the feeling that few people appreciate this, least of all the friend who woke me up late last night with a call for romantic advice and instead received an exegesis on what Dorothea's choices in love represent. I chuckle as I recall it. Beyond, the trees toss restlessly in the wind. Suddenly, a

deep metallic alarm sounds, and draws me out of the world in which an author

can admonish her reader to “inquire into the comprehensiveness of her own

beautiful views, and be quite sure that they afford accommodation for all the

lives which have the honour to coexist with hers,” without seeming at all

preachy.

I’m sitting on my balcony, reading Middlemarch. It strikes me as a rare

treat, two or three times a year, that enough time has elapsed since I’ve read

it last for me to feel it freshly, and I pull it off my bookshelves and delve

into its wisdom. I have the feeling that few people appreciate this, least of all the friend who woke me up late last night with a call for romantic advice and instead received an exegesis on what Dorothea's choices in love represent. I chuckle as I recall it. Beyond, the trees toss restlessly in the wind. Suddenly, a

deep metallic alarm sounds, and draws me out of the world in which an author

can admonish her reader to “inquire into the comprehensiveness of her own

beautiful views, and be quite sure that they afford accommodation for all the

lives which have the honour to coexist with hers,” without seeming at all

preachy.

My phone is

lit up with a flash flood and storm alert. I turn off the alarm and toss it

back inside, onto my carpet, and put George Eliot down with respect. I need to

grade sixty essays tonight. My students have written about the drug problem in

America, including psychological and physical effects, and I promised I’d

return them so that we can finish drugs before we start racism tomorrow. We lead an exciting life. I begin

to read through the essays.

“I have 4 aunts and 2 uncles and they all

smoke weed. Out of 6 of them only 2 graduated from high school, because they

got lazy and didn’t want to finish school but get high.”

“My sister’s father was on a drug

called water and he became abusive and harmed others.”

“I lost my grandpa because someone

tried to fight him because of drugs, and when my grandpa won the fight, the man

retaliated; shot and killed my grandfather on the steps of a crackhouse. This

proves that drugs…”

I put the papers aside for a moment. Although there is something incredibly

life-affirming about reading these essays and picturing the three motivated,

successful students who wrote them, students who rose out of the embers of

others’ lives by their own sheer willpower, they hit me too heavily. Their

matter-of-fact acceptance of ugliness in their lives brings to mind the glass

of the door shattered in the gym today, by students who kicked it in because

they were mad at being locked out, and my brilliant student who told me glumly in third block that she can’t go to OSU after all—Chapel Hill gave her a better scholarship, even though it doesn’t have her desired major. I cast about for

something else to think of.

A memory

flits across my mind. Eight years ago, my friends and I crowded excitedly into

the auditorium in a women’s college in the Shomron to hear Rav Lichtenstein speak.

Rav Lichtenstein, one of the greatest minds of Modern Orthodox Judaism, who had

a PhD in literature and speckled his sichot with poetry. I try to

remember whether he spoke in Hebrew or English on that day. Odd, not to

remember a language. I wonder whether at his funeral tomorrow someone will

quote Milton, and whether they will read him in English or Hebrew. I hope so—I

hope someone realizes that this great leader’s teachings flowed sweeter through

his poetry.

A memory

flits across my mind. Eight years ago, my friends and I crowded excitedly into

the auditorium in a women’s college in the Shomron to hear Rav Lichtenstein speak.

Rav Lichtenstein, one of the greatest minds of Modern Orthodox Judaism, who had

a PhD in literature and speckled his sichot with poetry. I try to

remember whether he spoke in Hebrew or English on that day. Odd, not to

remember a language. I wonder whether at his funeral tomorrow someone will

quote Milton, and whether they will read him in English or Hebrew. I hope so—I

hope someone realizes that this great leader’s teachings flowed sweeter through

his poetry.

On the far

side of my desk I have painted a poem. This afternoon, a student came for

tutoring during my planning period and snapped a picture of it on his phone.

“I’ve read

it a million times,” he told me, “while I sit here and wonder what it means.

I’ve been meaning to take a picture for a while.” He needs to finish writing

his essay on drugs. He excelled in the debate. But his essay was a paltry unfinished

paragraph, born of his reluctance to write, and I told him he owed me an essay.

“I guess

I’m afraid to write. I’m afraid that I will make a mistake and it will be

written forever.” We talked about the beauty of editing, of slashing out the

dross and leaving the gold. He bent his head over his desk and attacked his

paper with good will. By the time the end-of-day announcements came on, he was

finished, and eager to talk.

“What does

articulate mean?”

“It means

knowing what you want to say and saying it well, sharply, clearly, perfectly.

Why?”

“You wrote

it on my first draft, when you said if I’m this articulate in speaking, I can

write, too, I just have to figure out how to make it happen. But I wasn’t that

articulate always—I used to be really—to not be confident. Now I’ve mastered

speaking, maybe I should try to master writing.”

I played it

cool, rubbing my ear casually to stop the trumpets from blaring. My student

will try to master writing. “Yeah. I’ll help, if you like.” We discussed some

possibilities for creative starts.

“You know,

the award I got from you this year, that was the first time I got one in like,

three years.”

I’m astonished. “How is that

possible? Are you the same in your other classes as you are in here?”

“You mean, like participating? No,

I guess not. It’s because… it’s because of conformity, I guess. Nobody really

cares, so I don't either. I don’t really bother. I feel safer being myself in here.”

“Huh. That’s good. I'm glad.” I'd like to say me too, but refrain.

“Yeah. I

don’t know what I was afraid of, before. Maybe… there’s this line somebody once

told me, that our worst fear isn’t about being inadequate… I can’t remember

it.”

“Yeah. I

don’t know what I was afraid of, before. Maybe… there’s this line somebody once

told me, that our worst fear isn’t about being inadequate… I can’t remember

it.”I can. As we head out into the sparkling afternoon sun shower, I tell him, “Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure.” My student hitches up his backpack jauntily and waves goodbye, secure in the joy of confronting his deepest fear.