Yesterday there was a red suitcase without any apparent

owner on my bus. A passenger asked whose it was. Nobody claimed it. Slowly,

people began to freak out. A scared Russian woman requested a

translation from me: “it’s a bomb scare, they’re frightened of the suitcase. It’s not

yours, is it?” It wasn’t. There was a range of reactions. The teenagers in

front of us were especially hysterical and began the general exodus off the bus

at the first stop we reached, while the guy in front of them was totally calm

and didn’t even take off his heavy-duty headphones as everyone shouted, “who

owns the red suitcase?”

|

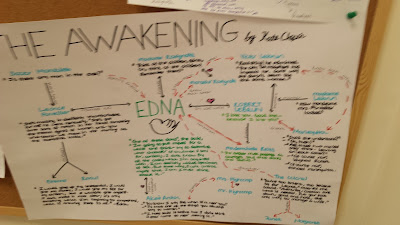

| Setting Map of The Awakening |

It was his, of course.

The driver got kind of mad, but everyone calmed him down,

and the girl who’d first asked whose suitcase it was sat down and began flirting

with the owner. I felt slightly sheepish, but also glad I’d kept my cool and

hadn’t gotten off the bus. There was a strong sense of camaraderie throughout,

as though, if we were all going to die in a few seconds, we wanted to do it

cheerfully and together. And if we weren’t, well, we had a good story. After

two months of attacks, the Israeli attitude towards violent death by terrorism has

evolved into a team-building activity.

Someone asked my Palestinian student, “are you going to the

climate march in Kikar Rabin Friday?” and he responded, “Hell no! I’m not going

into Tel Aviv. Someone might think I’m Jewish and stab me.” A little

introspection on who “someone” is might be interesting for him. That's also probably the best evidence against Israel being an apartheid state I’ve ever

heard; we’re integrated enough that even the people determined to kill us can’t

tell us apart. Don't let that fool you, though-- there's a great distance between not being an apartheid state and true equality.

|

| Character Map |

The Palestinian students in my classes are making close

friends with the Israelis, who grok them better than anybody except students

from other Muslim countries. Many are also truly struggling with their

identities as Palestinian in an Israeli school. It would help if we had more

Palestinian staff—two Arab teachers are not enough for our school’s mission. The

administration has assured me that they’re working on getting more. I think

it’s urgent. At times, I’m very conflicted about my own identity plopping up

silently in my head while working through ideas with my students; they need

more teachers who share their accents and discomfort with Israeli soldiers and

naming of Yom HaAtzmaut as the “Naqba.” I can make a safe space for that in

class, but I’m silently uncomfortable in the midst of my matter-of-fact

mannerisms. And I can’t imagine how the all-Israeli teachers who spout political diatribes in the staffroom are dealing.

We had the oddest moment in a staff meeting, when one

teacher wanted to space midterm exams out to make them easier for students. It

gave me a moment’s mindboggling insight into an Israeli education system that,

while being just as test-based as the American, doesn’t actually regulate those tests with any kind of

intensity. Whereas in the States I always felt like education was some kind of

holy crusade, here classes are a distraction from the important business of

kvetching about students. Teachers wander into class with as much preparation

as a TFA cadet—that is to say, a lot of contradictory nonsense that they

espouse very firmly, and that confuses the students to maximum effect. Say what

you like about teacher education programs, my traditional Masters was the most

useful teaching instruction I had (besides, of course, trial-and-error learning

on my poor students). But the Israeli system doesn’t seem to begin to approach

the things we take for granted in the States: student-centered instruction, and

investigative learning, and diverse methods of instruction, all appear brand new

to them.

|

| Thematic and plot maps |

I recently created a new way to teach my students how to

support their ideas with evidence. I put two theses that I want them to

consider on the board (for example, “The

Awakening is a modernist text,” and “The

Awakening is a naturalist text,” or “birds are a symbol of femininity in

the text” and “cigars are a symbol of masculinity in the text”). They don’t

have to be opposed, just related. The kids work like mad for ten minutes,

finding support for each statement in the book, and at the end, two names pop

up beneath each thesis—they’re going to have to convince the class of theirs in

two minutes or less. They take it very seriously. They don’t clap at the end of

a speech; they pound the table like they’re at some hoity-toity board meeting. Their

intensity in learning is incredible.

Today, they practiced for their oral exams. Their eager

explications filled the room as they gestured and graded each other in

partners. As they left the room, I pulled an incredibly cheesy teacher move,

and stood at the door, high-fiving every kid as they exited. Well, some I

clapped on the shoulder, and one I elbow-bumped (Hassan is always original).

Every so often, something reminds me that I’m one of the adults that stand

between them and the abyss of despairing teenagehood, whether they are tossed

by low body-image or depression or a national identity crisis or genuine grief,

and I want to wrap them up with an affirming love that will power them through.

That part of teaching, at least, is the same wherever one goes.

No comments:

Post a Comment